by Tosh McIntosh

During the long journey to publication of Pilot Error, which from start to finish took eight years, with 13 major drafts and many more small ones, I worked with a freelance editor in New York who had been an acquisitions editor with a major publisher.

At one point deep into our collaboration, he suggested I read some of the books in Ross Macdonald’s Lew Archer series to study how the author managed to shift the private investigator genre from the style of the ‘30s and ‘40s into the ‘50s. According to the editor, the character of Lew Archer defined a new breed of PI hero, and the editor wanted me to understand what he called total characterization.

That topic deserves a post of its own, but for my purpose here, I’ll focus on one aspect that relates to the title above, which is character perceptions. That may initially seem to be a spurious connection, so please bear with me for a moment.

You’re writing a scene in which the POV character walks into a room for the first time. It’s the office of another character who is an opponent, and there will be tension and conflict based on their opposing goals.

At that moment, this office is nothing more than a white curtain behind the stage upon which the two characters will play their roles. You could leave it like that, and your target readership may not notice or care if they do. But when this scene is part of a submission for NIP Roundtable, you might well receive comments about the lack of setting because it’s one of the structural elements of fiction, and we’re there for the expressed purpose of collaborating on the mutual goal of improving our individual expressions of the craft of writing.

You conclude the comments are valid and decide to fix it on revision. Turns out you’re good at writing setting, and the new scene has three long paragraphs about what the office looks like, with rich and colofrul details that allow readers to create a detailed mind picture of the stage.

Later in the revision process you happen upon an online course taught by Holly Lisle, known as “How To Revise Your Novel,” or HTRYN. And in it, you come across something that for the purposes of this post I’ll call “the five-cent principle.”

Applied to this scene, the principle might focus on a vase you have described for readers. It’s sitting on a shelf in a bookcase in the office. It’s not just any vase, but a gorgeous antiquity, a one-of-a-kind work of art. You put it there because you happen to know something about the world of collectibles, and particularly that in the fall of last year, an Imperial Quianlong-Era Chinese vase sold at auction for $24.7 million. You’re not describing that vase, but one like it, and you do so in great detail.

image credit: Skinner, Inc. via Bloomberg (Note: For a larger view of this spectacular work of art, click on the image. You can return to this page with your browser’s back button)

According to Lisle’s principle, the fact that there’s a fictional vase on the shelf is worth five cents, and each additional detail about the vase adds another five cents. Let’s say that before you’re through it’s worth $5.50, and the question is whether it’s too pricey for the scene. And the answer is . . . it depends.

If the description flows onto the page because you think including setting is important for your work, you’re good at it, and you have background knowledge about these ancient works of art, Lisle’s principle would suggest it costs too much. You’ve devoted text time in the scene to something that doesn’t matter to the story, and in effect it’s nothing more than an author intrusion.

But what if (a great concept in fiction, right?) your POV character has an interest in the topic of Imperial Chinese vases, you’ve established that in advance, and inserting it here isn’t like dropping it through the ceiling of the office? And most important, the fact that the other character has the vase means he’s either extremely wealthy or wants to appear to be by displaying a forgery? Now the observation flows to readers from the logical perceptions of the POV character.

And to connect this principle with the editor’s emphasis on the importance of total characterization, this perception by the POV character is also selective. The office is probably filled with items the character could notice but didn’t because the author used setting to reflect characterization, and in this case, contribute to what really matters, which is plot.

In closing, I want to credit our very own Brad Whittington, who just yesterday shared with me what he referred to as an alternate example Lisle’s five-cent principle. It’s also more literary, which we expect from Brad, of course.

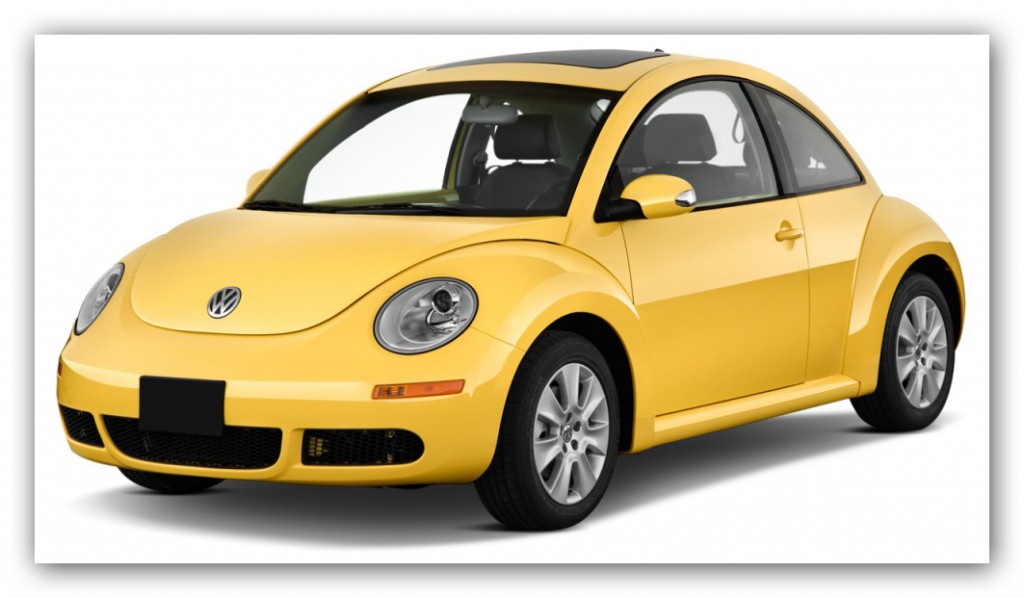

The example comes to us from Frank Conroy, who once scolded a student for using irrelevant details in her short story. He said: “The author makes a tacit deal with the reader. You hand them a backpack. You ask them to place certain things in it — to remember, to keep in mind — as they make their way up the hill. If you hand them a yellow Volkswagen and they have to haul this to the top of the mountain — to the end of the story — and they find that this Volkswagen has nothing whatsoever to do with your story, you’re going to have a very irritated reader on your hands.”

To help us avoid that revolting development in our writing, we should always remember Conroy’s Yellow Volkswagen Rule.