by Tosh McIntosh

Anyone who has participated in a critique group has heard someone make a statement like the title of this post. It’s as if there are inviolate rules out there, and everyone ought to know better. I’ve heard discussions in which writers defend their decision to bend or break a rule because their favorite authors do it all the time. That usually receives a counter like, “Well sure. NYT bestselling authors can get away with anything.” This exchange raises the question of whether the subject authors are being given a free pass to break rules because they sell lots of books, or if there’s another factor at play that we aren’t recognizing in a Roundtable session.

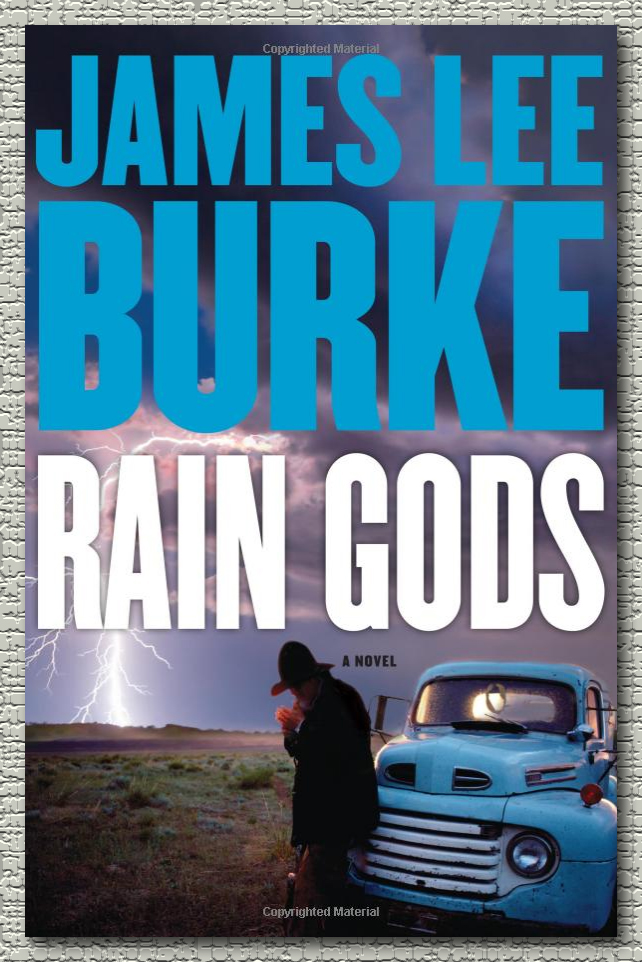

My current pleasure reading list has included the series of Dave Robicheaux novels by James Lee Burke, and I just began reading a sample of the second book in another Burke series starring Hackberry Holland, titled Rain Gods. This post uses the opening of that novel to illustrate a point that I think we need to keep in mind when evaluating how well any given story begins.

Chapter 1 begins with an unnamed young man calling 911 to report shots fired. After a scene break, a “tall man in his seventies” (Sheriff Hackberry Holland) arrives at the location reported in the call and finds evidence of a horrific criminal act. After another scene break, Pete Flores shows up at his rented house where his girlfriend Vickie Gaddis lives with him, and he learns that some men had showed up there last night while Pete was away. One of them was named Hugo, and that’s when we learn that Pete must have been the young man who called 911, and he’s gotten into some really dangerous stuff that’s a lot worse than trafficking in dope.

Chapter 2 begins in the POV of Nick Dolan, who runs a skin joint. Hugo Cistranos has just walked into the bar, he’s there to see Nick, and that isn’t a good thing.

After a scene break, we’re in Hackberry Holland’s POV again, and we get to see a rewind into what happened at the crime scene when Federal agents had showed up to take over the investigation. After another scene break, we get backstory on Hackberry’s past from the first novel in the series, then shift to current story time as he reflects on the events of the past 24 hours before heading into his office, where we meet a female chief deputy named Pam, who informs Hackberry that an Immigration and Customs Enforcement guy named Clawson had just left the office after dropping off a business card. Hackberry calls Clawson, and the beginnings of a very contentious interaction between these two characters begins to unfold.

The sample ends here, and to say that Burke has hooked me would be a gross understatement. It may not hook you in the same way because you don’t read these kinds of novels. But just like when reviewing a NIP submission in a genre we don’t read for pleasure, I believe there are valuable benefits to be had by concentrating on the story strategy, scene selection, and juxtaposition of scene, sequel, and backstory in this relatively short sample penned by an author who I think is a master at enveloping the reader in the fictive dream from the first word.

If you have a Kindle or a Kindle application on another device, you can download this sample to take a look with the following in mind, and you just might buy it:

- What percentage of the total text time is devoted to current story and backstory?

- When Burke uses sequel to delve into the POV characters, can you identify how he reduces psychic distance to put you within the character’s skin?

- Are you left with a compelling story question?

- How about conflict and tension?

- Too many named characters, or are they drawn well enough to imprint their potential roles in the story?

What are you waiting for?